Home > Our Impact > Electric Power

Electric Power

Electric vehicles are rapidly becoming a common sight on our streets, and industries are increasingly turning to electricity for more processes. As new sectors electrify, demand for power will increase. It is all the more important that this electricity be clean. Fortunately, across the globe, renewable power—especially wind and solar—has become the most affordable form of electricity. However, misconceptions persist about the reliability and benefits of renewables. Setting the record straight is thus crucial to making clean energy the backbone of our power supply. By providing clear and accurate information and tailored solution-oriented advice, we can help ensure that the transition to clean energy continues to accelerate, moving fossil fuels out of future energy plans.

Supporting the swift deployment of renewable energy sources

Wind and solar are already the cheapest sources of energy worldwide. To ensure their accelerated deployment, however, requires continued contribution of private investors. A transparent, stable, and predictable policy environment is a prerequisite for stimulating private capital inflow. Key instruments of such a framework include renewable energy targets, support schemes to ensure revenue certainty, and renewable energy auctions, alongside incentive schemes such as net metering, tax rebates, and financial support.

Policy spotlight

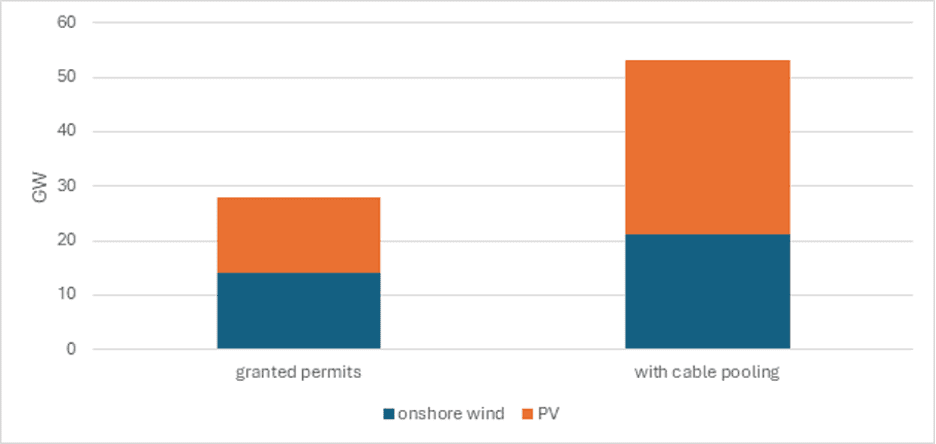

With Forum Energii’s support, Poland adopted a policy allowing connection of multiple renewable sources to one grid access point, called cable pooling. This solution paves the way for adding 25 GW of wind and solar capacity to the existing grid without additional expansion costs and—if fully exploited and used to replace electricity production from hard coal—could help cut 18 million tons of CO2 emissions per year.

Building strong and smart grids

Power grids—the backbone of electricity systems—face increasing demands on the path to climate neutrality. They must not only connect to expanding renewable energy sources, but also support new technologies such as electric vehicles and heat pumps. Furthermore, reinforcing or building new transmission corridors and integrating new, smart technologies to transport more electricity will be crucial. Responding to this challenge requires an infrastructure overhaul and significant investments. Developing comprehensive and ambitious action plans and regulatory frameworks is thus essential. These should address four dimensions: planning, delivery, financing, and the optimal use of existing (especially distribution) networks—all supported by digitalization.

Policy spotlight

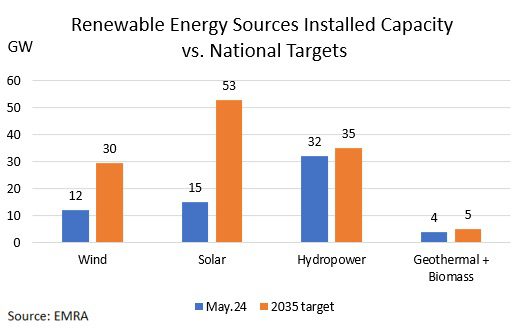

SHURA Energy Transition Center’s work has informed key energy policies in Türkiye, leading to the government announcing an investment of $10 billion in green grid infrastructure by 2030. This investment is critical for achieving the country’s target of increasing the share of variable renewable energy sources from 16 percent to 32 percent by 2035.

Unlocking flexibility

Flexibility—the ability to adapt to changes in supply and demand—is at the core of climate-neutral power systems. It can help offset the variability of renewable energy sources like solar and wind, ensure security of supply, reduce costs for consumers, and support grid operations. Relevant technologies for supporting flexibility include pumped storage hydropower and battery storage. Incentivizing flexible demand is another key strategy. The rapidly increasing electrification of different parts of society—from heating to industry to mobility—creates significant potential for flexibility, such as via batteries for electric vehicles. Electricity market design that rewards flexibility can help unlock this potential, along with standards for end-user devices and systems so that they can operate together seamlessly regardless of manufacturer.

Policy spotlight

With contribution from Agora, Guangdong adopted a policy titled “Work Plan on Promoting Pilots of ‘PV + Buildings’ Across Counties in Guangdong,” setting total installed photovoltaic capacity targets from over 1,250 MW in 2024 to over 2,000 MW in 2026. The policy is expected to boost distributed renewable development and alleviate grid bottlenecks, especially at the county level.

Fostering a just transition away from fossil energy

Coal-fired power generation is increasingly being phased out of power systems for economic and environmental reasons. However, in many countries and regions, moving away from coal leads to profound structural change. Proactive, transparent, and concrete strategies are thus needed to mitigate the transition’s economic and social impacts. Building trust in renewables-based power systems’ ability to provide a secure supply is also critical to drive the transition from coal to clean energy. Engaging with stakeholders and developing fact-based and credible pathways tailored to local circumstances can help achieve this.

Policy spotlight

The Public Affairs Research Institute drafted the chapter in South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment plan that aims to accelerate renewables deployment at the municipal level. Through measures such as upgrading and modernizing municipal distribution grids and restructuring tariffs, the plan is expected to significantly increase the renewable energy share and improve access to affordable and clean electricity.

Ensuring equity

Because the transformation of energy systems fundamentally affects all parts of society, strategies need to be just and equitable to succeed. Decarbonization efforts should thus include measures designed to ensure that all communities benefit from the transition, while minimizing potential negative socioeconomic impacts. Broad participation, engagement of stakeholders, and targeted support for disadvantaged groups can build trust in renewables-based power systems. Strategies should also be tailored to specific regional and political energy contexts so that the needs of diverse stakeholders are adequately addressed.